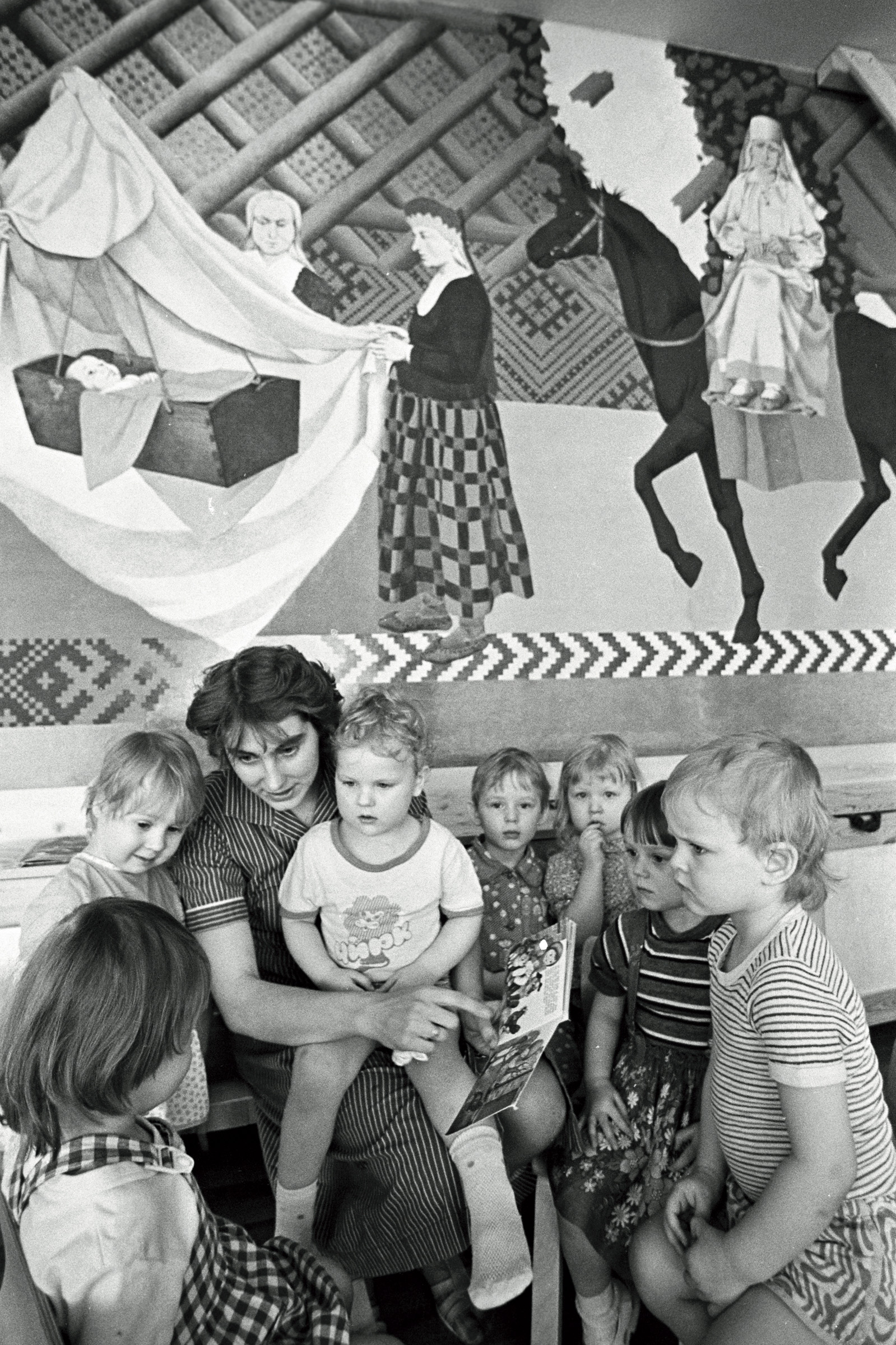

Fresco pannels in Väätsa kindergarten

Year of completion: 1987

Address: Järva County, Väätsa Borough, Kooli 12

Author Andrei Stasevski

Fresco

220 x 600; 220 x 600 cm

Not listed as a cultural monument

The second half of the 1960s saw a surge in monumental art studies in the Art Academy thanks to changes brought by the decade and Lepo Mikko’s supervision. In the 1970s, the role was passed to Dolores Hoffmann, who had already conducted the teaching of traditional techniques in monumental painting as a master of the department during the mid-1960s. A masterful example of using a historical technique that requires distinct skills is the diploma project of Ukrainian-born Andrei Stasevski – two large-scale fresco pannels in Väätsa kindergarten. During the Soviet Era, the Estonian Academy of Arts was attended by students from numerous other republics of the Union, and foreign students of the painting department often specialised in monumental painting. Ideologization and Soviet propaganda, however, is not present in their artworks, just as it is missing from the paintings made by Estonian students.

The art institute of the time had friendship and patronage ties with the 9th May collective farm in Väätsa, which was one of the most successful farm enterprises in Estonia thanks to chairman Endel Lieberg’s management. Students visited Väätsa every fall to harvest potatoes as an act of patronage, as was the custom during the Soviet Era, but wide-ranged art-related cooperation was born as well. Besides Stasevski’s frescoes, Väätsa also has other examples of monumental art created by former students of the art academy: a ceramic pannel in the cultural centre and Urve Dzidzaria’s renaissance-style fresco in the local guesthouse.

The pannels in the kindergarten cover the entire long wall opposing the great hall’s windows on the first floor. They depict a historical village environment but even upon close inspection, it remains unclear exactly what nation this milieu is representing. One can recognize men in Mulgi style robes and muhu crosses in ornamentation strips, while the celebratory clothing of the women is more laconic and elusive, and the characters’ appearance seems rather Slavic. On closer inspection, it can be seen that the artist has planned the Estonian vertical skirt strip when pressing the frescoes’ cartone paper into the damp plaster surface, but has apparently abandoned the idea to avoid making the composition too colourful. The piece has an intense effect with its extremely warm reds and yellows, but the fine balance of the alternating ornaments and figures allows the viewers eyes to rest. Daily life and its fashions-customs seem to interweave with the world of dreamlike beliefs in the atmosphere created by the talented figure painter. The women in celebratory garments and the slightly Chagall-esque village violinist are as if floating in air, the solemn scene surrounding a child in a cradle, and other fragments of the image begin to open the door into the mystical world of folklore.

Employees of the kindergarten have acknowledged the paintings and they have remained untouched by renovations. The pannels have some scratches and damage to the surface of the paint but their overall condition is good. Despite the feet of the floating characters in the painting hovering just above the heads of children in group photos taken at the kindergarten’s parties, one can hope that the piece will continue to remain in its place. The fresco is made to last with the passing of time, and when such a masterful technical achievement is accompanied by an evidential artistic value, then the artwork is worth protecting.

Reeli Kõiv