Plaster Reliefs in Räpina Ühisgümnaasium

Year of completion: 1961

Address: Põlva County, Räpina, Kooli 5

Author Mari Tiilen

Plaster

Not under conservation as a cultural monument

In the 1950s, the war-torn world began rebuilding itself from the industrially manufactured building panels, the residential estates built from which enabled fast alleviation of the egregious housing shortage. However, a problem with the fast and cheap architecture arose shortly – it tended to be mute and monotonous. This inspired the attempts to decorate the post-war architecture with visual arts, a method that had also been employed in the case of pre-war modernism. Soon enough, public space everywhere began to be filled with monumental and decorative artworks in various techniques. The post-war modernist architecture became a canvas of a sort, on which one could seek their roots, express views, exercise artistic ambitions, realise the aesthetics enforced by the foreign power or all the aforementioned at once.

In the Soviet Union, such monumental artworks had to take on the role of a herald, which was previously played by the grandiose Stalinist architecture. In Soviet Estonia, the decoration of buildings initially had the tendency to have clumsy results. The illustrations meant for invigorating buildings often had a burdening or out of line effect instead. Even art critic Ressi Kaera admits in the 1961 newspaper Sirp ja Vasar(Hammer and Sickle) that although decorative art in the public space is developing for the better, the whole undertaking is still lacking in organisation.

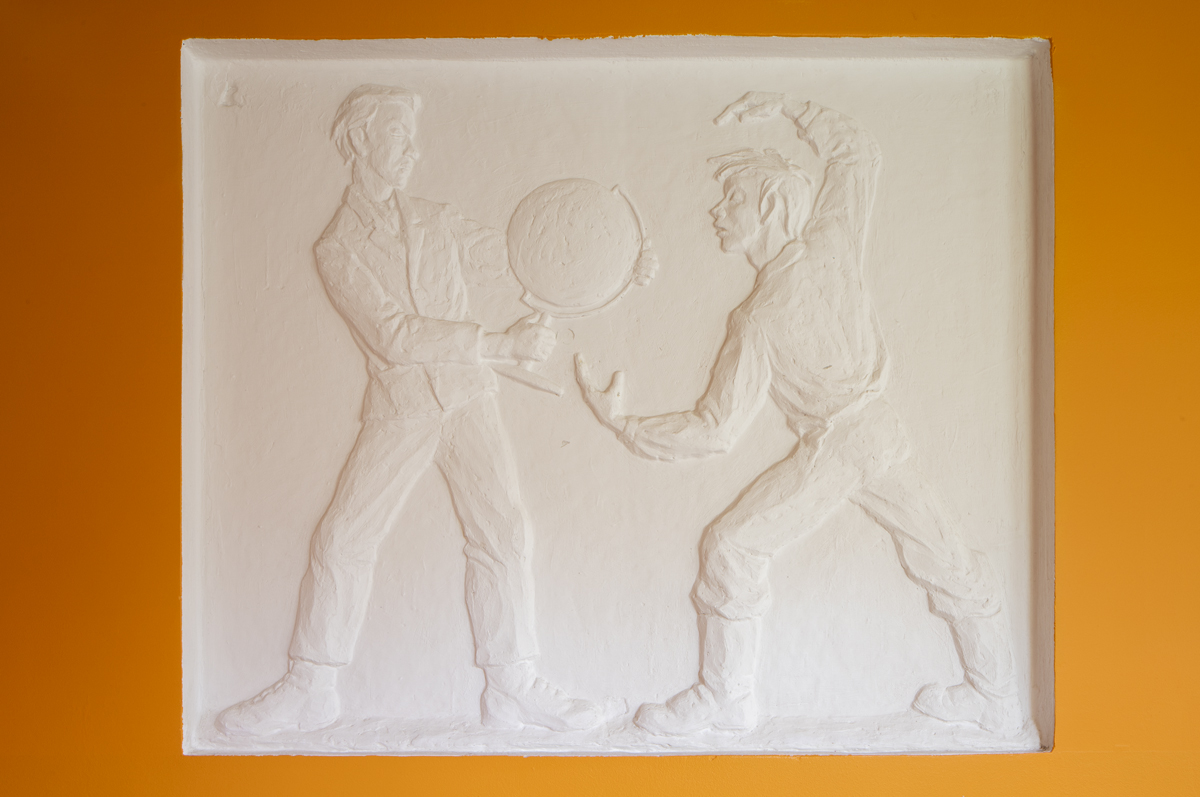

In 1961, when pursuit of decorative arts was rapidly growing, the current Räpina Ühisgümnaasium opened its new modernist building. The Tartu Art Fund mediated three artists from Tartu to decorate the schoolhouse: sculptor Aulin Rimm designed the metal composition, painter Varmo Pirk designed the stained-glass windows, and sculptor Mari Tiilen designed the plaster reliefs. The stained glass and metal composition were evaluated quite graciously by Ressi Kaera. Tiilen’s plaster relief’s, however, that depicted scenes from Oskar Luts’s Kevad (“Spring”), made Kaera quite cautious. “One cannot have anything bad to say about the stories of Toots, with them belonging to our classic literature. But essentially, the reliefs could be replaced with graphic pages without any lesser success. In the case of ornamentation, as well, more effective forms exist. Besides, plaster is no commendable or permanent material,” she says about the initially light-blue toned reliefs.

Ironically, Mari Tiilen’s plaster reliefs have survived in Räpina Ühisgümnaasium today, while artworks created of more permanent material such as metal and glass have not.

Anu Soojärv